Interview: Mariusz TRELIŃSKI on "Boris Godunov"

―You initially studied film direction and became a film director, with many movies to your credit. How did you get into opera directing? Did you already have an interest in opera when you were studying film?

―You initially studied film direction and became a film director, with many movies to your credit. How did you get into opera directing? Did you already have an interest in opera when you were studying film?

Music was the key. From the very beginning, music was the starting point in my films. It brought the atmosphere, the rhythm, the energy and even the colour of the sequences in question. Music contains all these elements; you just need to listen to it. Of course, this is a wildly subjective process, but for me it is a key signpost. The music is the vector that gives all the directing solutions. The characters of the story are given the second place, and the words - only the third place, which is extremely important in the case of opera, where sophisticated and clever librettos are very rare. The music therefore decides everything. My decision to do Madame Butterfly, my first opera, was purely intuitive. There was a lot of whim and simple curiosity involved. At the time, I was attracted to minimalism, so the Japanese reference points of this work were tempting. The result was a very chill, meditative performance that was, to my surprise, a great success. This staging was shown dozens of times on almost all continents, and it made me an opera director overnight.

―At the Teatr Wielki - Polish National Opera, of which you are Artistic Director, many of your productions have attracted international attention, and you have also directed opera at major opera houses and music festivals. Is your method in directing movies and opera similar or totally different? What for you is the most important principle when directing opera?

Finding the central issue that focuses my attention, an issue that is still alive and poignant today. Opera, because of its longevity, often becomes an antique museum of conservative views and clichés. But if the music is alive, it is worth finding an element of freshness in the story itself. When I manage to find such a topic, I take the title. Without this, the expedition is meaningless. The triviality of the message or the staging can even make the music dead. Yet, with exceptionally good performances, one can then simply close one's eyes. In the case of my films, I always wrote the script, so the problem of the story being up-to-date existed to a lesser extent. Sometimes, however, I missed the dimension that music gives. Lately, I have been fascinated by films that are by design devoid of music, in which the rhythm comes entirely from the editing of images and sound. The films of Dogma or the Dardenne brothers - they become music themselves.

―The pandemic has had a devastating impact in the opera world. During the pandemic, you had to rework Die tote Stadt for La Monnaie with almost no sets utilizing visual images. Has this experience of directing in pandemic times influenced your way of thinking about directing opera?

It has had a negative impact. I come from film and think with images. Both in cinema and opera, they are the main tool of interpretation. Being cut off from images was for me like a painful castration. Pandemic, however, was an interesting moment of tranquility, contemplation and focus. I think that this experience of stopping time, of being cut off from the world, from meeting people, which was very painful, often even dramatic for many people, was fascinating and invigorating for me. I suppose I had simply lived too intensely before.

―You first collaborated with Kazushi Ono in The Fiery Angel in Aix-en-Provence in 2018 (which I had a great pleasure of attending). How was it to collaborate with Maestro Ono on this production? How do you see him as a conductor?

We worked on the same premiere earlier in Warsaw. Kazushi Ono is undoubtedly a great personality and an extremely humble man. Holistic, total thinking is characteristic for his work. The opera, despite its three-hour duration, is a unity for him. The dramaturgy of the whole, the leading of a single ascending line, becomes crucial. The second important thing is his highly original approach to Russian music. While preserving its originality and distinctiveness, Ono opposes its sentimentalism and tendentious emotionality. This gives it a completely different supranational character. It is very close to me, and I was looking forward to this meeting, having in mind many of my past performances with Russian conductors.

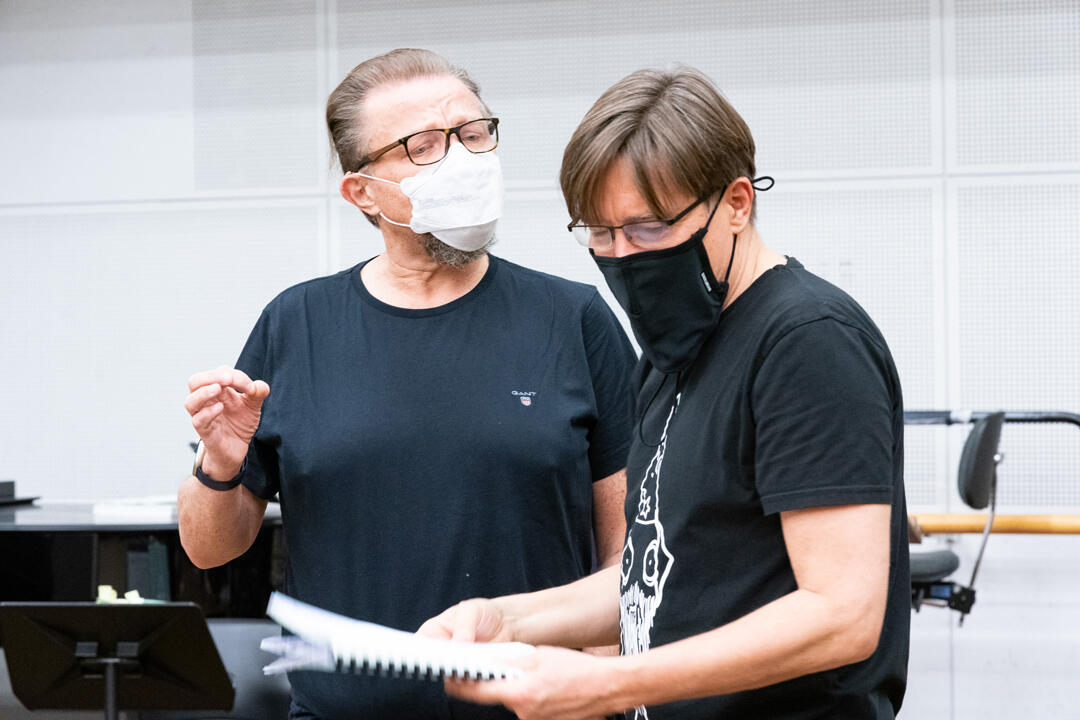

From the rehearsals of "Boris Godunov"

―In April, the Polish National Opera made the decision to cancel this new production of Boris Godunov in protest to Russia's invasion to Ukraine, so it will have its premiere at the New National Theatre, Tokyo. I realise it is a sensitive issue, but what is your take on this matter? Have you made any changes to the production since Russia's invasion to Ukraine?

As director of the National Opera, there was no doubt for me that, at the time of Russia's brutal assault on Ukraine, this production should be stopped. The emotional force of the events was so great that even simply listening to the Russian language caused discomfort. There are quite a few people from Ukraine in our chorus, so it was also important to respect their feelings.

Godunov is commonly associated with Russian imperialism and nationalism. This is how it is staged in Russia, with Tarkovsky's famous staging as a key example. However, the work is a great fresco that encompasses many points of view and allows for a critique of this way of thinking. It did not take Putin's invasion of Ukraine to see the nationalism and ruthlessness of this way of thinking, especially when you live in Poland. My intention from the beginning was to oppose these trends.

Godunov, both in Pushkin and Mussorgsky, is a character marked by a false and painful choice. He decides to murder the Tsarevich boy, in order - as he understands it - to save the country. The theme: building an empire on the harm of a child, was also taken up by Dostoevsky. Although a dubious ideologue, this great writer was unanimous on this issue - nothing can be built on the tears of a child, as it will only cause evil. However, committing this act and analysing the ethical consequences that slowly come to him, Godunov, like Macbeth, becomes a wreck of a man who can never forgive himself. Evil remains evil. Even though Godunov is a broken, lost and bitter character, ending in collapse and madness.

―You have directed Boris Godunov before in 2008. In the 10+ years since then, how has your view and interpretation of the opera changed/evolved?

I did it three times, each time finding different motifs in the libretto. This time, the key to the narrative was to combine two characters: the son of Godunov and Yurodivy into one. Yurodiyy, or St Idiot, is a character typical of Russian tradition. Historically speaking, being insane, holy and unpunished at the same time, he could, like a shaman or jester in other traditions, accuse the Tsar and get away with it. In our staging, it is Godunov's sick, crippled son who is his chief accuser. In this depiction, the truth is more painful. His beloved son becomes his greatest enemy. A burning remorse.

From the rehearsals of "Boris Godunov"

―Although Boris Godunov is based on real events in Russian history, the broader themes such as the monarch's downfall or of people plotting for power are universal and could happen anywhere. How have you interpreted this story for this production?

For me, human being is always the starting point. This opera is epic on the one hand and focuses on the main character on the other. I find in it a truly fascinating description of the disintegration of Godunov's psyche. I subordinated the whole story to him. We are dealing with a subjective narrative and an attempt to enter his mind. It consists of his hallucinations, fears, predictions, guilt, love for his son and self-judgement. In our analyses, we focused on contemporary descriptions of the PTSD syndrome.

―One could say every character in this opera has his hidden agenda. Which character fascinates you most?

The meeting between Godunov and his son is, for me, the central axis of the story. The entire intellectual message is contained in it. The son becomes both a victim and judge and executioner. The figure of False Dmitry is also intriguing to me. The one who comes to clear the throne sows even more terror than Godunov.

The Set plan of "Boris Godunov"

―What attracts you about Mussorsky's music?

Its epic side. Its psychological chameleonism, which manages to express the thoughts of all social classes, together with the people represented by the chorus. It is often said of this opera that it is the chorus who is its main character. Its voice goes through all the phases from acceptance of the new ruler, through distance, rebellion and judgement. We are all looking hopefully for signs from Russia today where such an awakening and opposition to the war and Putin's rule might occur. Obviously, Russia, as a police state bloodily suppresses any unrest, but recent demonstrations of dissent, linked to military mobilisation, leave some hope.

―I understand the version you are presenting is an amalgamation of the 1869 version and the 1872 version. Could you explain the version you will be performing - is this for dramaturgical or musical reasons, or both?

The first version is certainly more compact dramatically. Undoubtedly, the second one has beautiful musical moments. Together with the conductor, we have developed a version that I hope combines the strengths of both versions.

Opera ❝Boris Godunov❞

On Stage 15, 17, 20, 23, 26 November.

See here for more information.